The worst news possible. This type of War Office correspondence was not welcome during WW1.

This is the original letter that T.A. Stephen's new bride Lydia received

after he had died of wounds in Belgium in 1917. They had only been married two

years.

Thomas Alexander Stephen, son of Armenians from Calcutta Stephen Simon

Stephen and Catherine his wife. They had died prior to his joining the war

effort.

Placed for sale as war memorabilia, I purchased it to save another small

piece of Armenian history from being lost. Note the crunched up creases on the paper. Could this have been Lydia's reaction to the terrible news? The agony of her loss, the cast aside letter screwed up into a ball and thrown away in disbelief.

And then retrieved.

Carefully and lovingly smoothed out and fixed to a piece of cardboard and stored. A focus for her grief.

T.A. Stephen's grandfather, Simon Stephens was the first recorded marriage

in the register of the Armenian Church Singapore and he was also co-founder of Apcar &

Stephens.

To read a detailed account of Armenians in Singapore and Malaysia, Nadia Wright's book 'Respected Citizens' is a must. You may also find her other book 'Armenians in Singapore: A Short History' also of interest. Obtainable on the same link.

Highlighting some of the lesser known, but just as important past Armenian characters in India. Those Armenians who have some sort of connection, or maybe simply buried in Calcutta and other locations in India, I re-create their lives and put them into short stories, at least as much as I am able to. The Armenians of India are unique and their stories need to be told. I hope this blog goes a little way to telling those stories. Armenian graves in India www.chater-genealogy.com.

Pages

Support The Stories!

Showing posts with label WW1. Show all posts

Showing posts with label WW1. Show all posts

19 November 2019

31 October 2018

John Arakelian D.C.M. Public Service Beyond Question - Dignity in the Face of Adversity

Last year I was fortunate to work with CAIA, the Centre for Armenian Information and Advice in London on their UK Armenians and WW1 project.

One of the stories I uncovered was about John Arakelian, his work with the British Intelligence in the Middle East and how he came to save 380 orphaned Armenian boys and girls in Baghdad. The original post can be found on CAIA's website above.

Following the project's completion I reproduce the story here on my blog because there is a Armenian Calcutta connection. (Please note the hyperlinks in [square brackets] do not work in this blog, please go to the end of the story to see the appropriate link.)

One of the stories I uncovered was about John Arakelian, his work with the British Intelligence in the Middle East and how he came to save 380 orphaned Armenian boys and girls in Baghdad. The original post can be found on CAIA's website above.

Following the project's completion I reproduce the story here on my blog because there is a Armenian Calcutta connection. (Please note the hyperlinks in [square brackets] do not work in this blog, please go to the end of the story to see the appropriate link.)

John Haig Arakelian D.C.M., M.M.

“…How?

How did I end up here?

In a jail in Wales.

How?...”

How did I end up here?

In a jail in Wales.

How?...”

On a cold

November morning in 1914, John Arakelian found himself being detained by the

Chief Constable of Newport Police as an ‘unregistered alien’, the underlying

accusation being that he was a German spy[1]. Held

for several days in a local gaol pending further enquiries, one can only

imagine how he must have felt. He could be forgiven for allowing his mind to

drift off and think about home; the warm breezes blowing across his land, the

golden hues of a setting sun reflecting on the surrounding hills and mountains

and the beautiful sweet smells hanging in the air, gently wafting up from the successful

family farm growing 84,000 fruit trees. And yet as he lay in his cell, he had

faith. Protesting he was not Turkish

but Armenian, recounting his already extraordinary military service in the

British Army, that faith was, eventually proved.

After

exhaustive enquiries by the Chief Constable into John’s life which revealed

nothing untoward, John was released without charge[2] and

allowed to return to what he did best. Serving in the British Army. He was in

Wales with his regiment, the 3rd Dragoon Guards, going about his

military business and following orders. It was his background, accent, looks

and his ability to speak six languages that made authorities twitchy. Yet, his

future military actions would prove unequivocally that he was loyal,

trustworthy and dedicated to the Crown. It’s just a shame the British

Government took so long to recognise this extraordinarily unique, fearless yet

humble Armenian when it came to his application for citizenship of the country

he had served for 17 years.

Born on the

1st April 1886 in Broussa near Constantinople, one of 10 children[3] (he had

two brothers and seven sisters), this staunchly Armenian family owned

considerable property and land. A large warehouse was used for the manufacture

of silk and the Arakelian’s ensured their workers had sufficient housing,

dedicating one large house, four smaller houses, eleven other houses and a

large bath house solely for their use. The family also grew several thousand grape

vines and fruit trees. It was a long establish and profitable farm, and they

helped the local community by employing as many people as they could between

their fruit and silk businesses.

John’s

father, Onig but also known as John, passed away when he was seven years of age

in 1892. The property and assets became the sole responsibility of his mother

Pilazou neé Andonian but the family soon fragmented and split up. His two

brothers Bedros and Vahram and two of his sisters as well as an aunt went to

England to live in 1894. John remained behind and attended the local protestant

school. Four years later his brother, Bedros returned to the family farm from

England and made arrangements for John to go and live there with him. By 1900 both

John and Vaham were in London, and with the guidance of their brother Bedros, John

was quickly enrolled at Professor Garabed[4] Thoumaian’s School, completing his education

at Clarence School at Weston-Super-Mare.

He took an apprenticeship in 1904 with an established and well respected firm

of builders, Foster & Sons of Bath

to learn machinery. He stayed for a year and moved to Glasgow finding employment

within the engineering department of a large company. He quickly realised this

was not the path he wanted to follow and boldly set about joining the Scottish

military by applying to the Royal Scots

Greys. His first posting was to the depot in Edinburgh. For the sake of

clarity, he ensured the military authorities were aware of his nationality and

that he wasn’t a British Subject.

This wasn’t something they were particularly concerned about and being

impressed by his physique as well as having the correct credentials, John was

posted to Tidworth Camp near Salisbury. Whilst there he caught the eye of a

General who complimented him on his “smart

appearance and good horsemanship[5].”

By 1908 John

was sent to India to serve and transferred to the 1st Royal Dragoons

at Muttra in Agra, his multitude of languages made him stand out from other

soldiers and he was able to converse locally in Hindustani. One day, the

Regiment Sergeant foolishly bet that if he could ride a particularly wilful and

stubborn horse without being thrown off he would be given a month’s leave. John

accepted the challenge with relish and, needless to say, accomplished the ride

with ease. He was soon planning his month’s leave to Calcutta.

John Arakelian and the Calcutta Armenians

In Calcutta

John would no doubt have gravitated toward the Armenian Church and the thriving

Armenian community of the city. It

wasn’t long before he was approached by a well known local Armenian coal mine

owner, C.L. Phillips[6] of

Kusunda Nayadih Colliery, near Dhanbad.[7] Phillips

was impressed by John and offered to purchase his discharge from the Army. John

agreed and went to work for another Armenian coal firm Martin & Co in the

Asansol/Dhanbad area, where he stayed until 1912. The Regiment Sergeant must

have been kicking himself at the loss of such a versatile and talented soldier.

But India was never going to be his last destination and after four years

there, John was keen to return to Broussa and to the family farm so that he

could take it over. He requested six

months’ leave from Martin & Co and sailed from Calcutta at the earliest

opportunity.

Constantinople – A Strong Bond

John felt

the pull of home more than ever and, rather than returning to India as he had

planned, he found a position in Constantinople as a PT instructor at the

American College. He wanted and needed to be close to home.

In 1912 John

purchased the shares and assets of his mother and siblings and became the sole

owner of the family farm, property and lands in Broussa. (Later, during WW1,

whilst he was serving in the British Army, the whole of the family property was

destroyed by the Turks because the Turkish authorities discovered he was

serving with the British forces.)

In November

1912 the Balkan War brought him to the attention of British born barrister Sir

Edwin Pears in Constantinople via Major Graves The Times correspondent of that city. Sir Edwin enquired of John as

to whether he would be willing to obtain information concerning the Balkan War

for English newspaper correspondents. John agreed and having met with the

newspaper representatives at the Pera Palace Hotel in Constantinople he was, in

John’s words:

“immediately arrested

by the Turkish authorities (at the instigation of a Greek spy), and after five

days confinement, was brought before the Turkish authorities War Minister,

Nazim Pasha, who was rather partial to Armenians.

After questioning me as to my

dealings with the English, he said that was it not for the high esteem they had

for my late father he would have me shot. However, he admonished me and advised

me to devote my abilities with the sword in instructing the Turkish

officers. On my release I was followed

by two detectives, but after outwitting them, I went to the British Consul who

arranged for me to be sent immediately to Egypt.”

It is

remarkable that John survived that close shave with the authorities, it is even

more remarkable that once in Egypt, his desire was still so strong he continued

to want to help the British where possible. With his Secret Service work in

Constantinople behind him and holding an introduction to the British Consul at

Alexandria, he was quickly appointed to the Egyptian Police Force. Once again

he made a good impression, this time of the Chief of Police and received praise

for his work. John spent only a year in Egypt, he was anxious to return to

Constantinople and he did just that in December 1913. With the assistance of

Sir Edwin Pears by way of another introduction, this time to the Standard Oil

Company, John was given the position of Assistant Engineer with the firm based

at the Dardanelles. He was responsible for a workforce of 200 men in

road-making that needed to be sufficiently well built to withstand heavy

machinery for the company. On one occasion and ever the observant professional,

he spotted Turkish forces in the distance moving heavy guns and military

equipment. He immediately informed Standard Oil Company and he was instructed

to close down the operation and return to Constantinople. He immediately

relayed this important piece of surveillance to the British.

A Second Period in the British Army

At the

outbreak of War in 1914 John was strongly advised by an English friend in

Constantinople to re-join the British Army. He registered at the British Consul

and was sent to England with a number of others also wishing to join. After reporting to Whitehall he was sent to

Newport in Wales where he joined the 3rd Dragoon Guards. He had only

been in Newport for a fortnight when he was suspected of being a German spy and

arrested. Three Court appearances and 22 days later he was cleared and

released. Remarkably, he chose to continue to serve in the Army and was sent to

Canterbury in Kent soon after this episode. Whilst in Canterbury he, and a

number of others, went before the town Mayor to swear and sign a declaration. John

believed this to be a naturalisation process, and little did he know that this

misunderstanding would once again cause him no end of trouble 10 years hence.

Extracted from

his Naturalisation application, a recount of some of his military career.

On

the 3rd April 1916 an attack was made on the first two front

trenches at HANNAH position. We advanced

about 3 miles the same day and captured FULAHYAH Redoubt and a communication

trench. I was responsible for taking the

communication trench, and seven prisoners who I handed over to General O’Dowda.

After this engagement I was promoted Sergeant. After the engagement at SANAIYAT

on the 9th April 1916 I was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal

for conspicuous gallantry to attending to, and bringing in wounded under rifle

fire in front of the enemy’s trenches. (See London Gazette, 14th

November 1916).

At

SHOOMRA BEND, I was in charge of the snipers and listening posts in no man’s

land, where I was successful killing one of the enemy snipers – a Sergeant.

Near this position, the late General Maude came to see me in the front

trenches, and complimented me for the good services I had rendered. At SHOOMRA

BEND I was asked by my Commanding Officer (Lt. Col. B. Macnaughten) if I would

signal the advance of the battalion from the parapet of the trenches when the

attach was launched. I volunteered to undertake this duty, and I stood in full

view of the enemy’s position for about six minutes to give the pre-arranged

three signals for the battalion to advance.

The

late General Maude was kind enough to give permission for me to search the

villages for any Armenian children held in captivity by the Mohommedans. By this means I collected about 380 Armenian

boys and girls at BAGHDAD, where an orphanage was formed by the Americans for

their welfare.

On

one occasion when in BAGHDAD assisting the Intelligence Department, and

collecting Armenian children, I discovered a large quantity of machine guns, ammunition,

explosives, searchlights etc., hidden by the Germans and Turks in one of the

houses.

I

volunteered to go to KUT and get into communication with General Townsend to

receive information and return to the British lines, but General Beach, Chief

of the Intelligence Staff considered the undertaking was too hazardous and

would not consent.

On

another occasion in BAGHDAD some 150 persons were collected together contrary

to orders, trying to create a riot. When

I arrived on the scene, I found an interpreter and British Military Police with

fixed bayonets endeavouring to arrest the offenders. Intervened and suggested to the officer in

charge that the police be ordered to unfix their bayonets and return to their quarters. I then coerced 75 of the principal offenders

to accompany me to the Police Headquarters.

They were eventually tried, five of the leaders being sentenced to 18

months hard labour, and the remainder to one month’s hard labour, and deported

from the country.

Again

in BAGHDAD I collected about 40 Turkish officers and Turkish government

employees, who by proclamation should have surrendered. I brought them to the Military Police

headquarters, where they were transferred to the Prisoners of War Camp in

India.

|

| Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum London. Men of John's regiment, the 6th King's Own (Royal Lancaster) Regiment bathing in a creek near Basra during the summer of 1916 |

John

recalls:

I joined the British Army in 1914 and

was demobilised 5th October 1920 at Constantinople. From here I was sent

to Armenia and served under the Armenian government. On the 11th

June 1921 I arrived at Baghdad and reported to the British Headquarters where I

was employed on intelligence duties under Major W.J. Bovill and transferred

later to S.M. Section under British government for supplying electric power and

water to Baghdad. On 5th November 1921 I went to Calcutta (India)

and was a student at the French Motor Company Calcutta until March 1922. I returned to Baghdad 23rd April 1922

as motor engineer but was unsuccessful in business. On the recommendation of

Colonel W. Dent I was employed by Iraq Aircraft Dept Royal Air Force where I

served until 1924. I was then transferred to Navy Army and Air Force institute

and resigned my position in August 1924 to return to England but unfortunately

I fell and broke my arm and owing to financial difficulties I was compelled to

remain in Baghdad until I left for England in May 1925. I have now nearly

completed 12 months in London since May 1925 but in all as my history shows I

have been about 17 years in England and in the British Army and with British

companies. 48 Cornwall Road, Harrow – May to June 1925. 134 Fellings Road,

Goodmayes – June 1925 to March 1926.

I have served under the British since I

completed my education in England in all, about 17 years, therefore I feel more

British and my record in the British Army is not in vain, I hope.

Naturalisation, Compensation, Honour, Acceptance - Disappointment

Initially,

at the time of John’s application for naturalisation in 1925, he hadn’t lived

in England for the minimum qualifying period of five years, and his application

was put back. However, because his “public

services were beyond question” it was suggested by a reviewing officer that

he should wait a year and apply again. John’s urgency for a successful

application was compounded by the fact that his personal circumstances were now

desperately dire. With a wife and young baby he was barely scraping a living as

a window cleaner at the Savoy Hotel in London. He couldn’t apply for his War

Compensation because he wasn’t a British citizen. Even the reviewing officer felt John was a

most deserving case

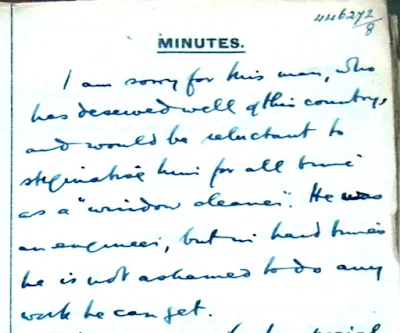

“I am sorry for this man, who has

deserved well of this country, and would be reluctant to stigmatise him for all

time as a “window cleaner”. He was an engineer, but in hard times he is not

ashamed to do any work he can get.”

John was

finally granted naturalisation in August 1926 at which time he applied for his

War Compensation. Unfortunately he was notified that it was too late and his

application was rejected. This would have been a bitter blow.

He and his

wife Angel, whose first child was born in Baghdad in 1925, went on to have at

least 2 more children who were born in London.

Following

the death of his wife Angel in London in 1933, John spent some time living with

his son and daughter-in-law in Hertfordshire. In 1959 he made one last voyage

to the Middle East. No further trace of him can be found.

He was a man

of great loyalty, dedication, commitment and dignity in the face of adversity

and, in his own words…..

Medals

Recommended for a Victoria Cross

which is the highest award in the UK honours system. He ended being awarded the

Distinguished Conduct Medal, the second highest award in the honours systems. He was

also awarded the Military Medal As well as the 1914-1915 Star,

the British War Medal 1914-1920 and the Victory

Medal 1914-1919.

Sources used for this blog entry:

AGBU on Flickr

Ancestry.com

Archive.org

BillionGraves.com

British Library

California Digital Newspaper Collection

Digital Library of India

Families in British India Society

Find A Will, Government Website

Findmypast.co.uk

Forces War Records

Hathi Trust Digital Library

Imperial War Museum

London Gazette

National Archives Kew

Newspaperarchive.com

Newspapers.com

British Newspaper Archive

Wellcome Trust Library

My thanks to

Diane John for assisting with document acquisition.

[1]

Western Mail, 3 November 1914, P.3

[2]

Western Mail, 17 November 1914, P.3

[3]

British Army WW1 Service Records, 1914-1920 for John Haig Arakelian – Personal

Statement

[4]

In June 1893 Professor Toumaian, who was also an Armenian Pastor was teaching

at the American-Armenian Christian College, “Anatolia College” in Marsovan. He and a number of other

Armenian intellectuals were detained by the Turks who believed there was an

“insurrectionary movement among the Armenian Christians”. During the trial, it

has been expected that Professor Toumaian and fellow teacher at the college Mr.

Kayayan, would be quickly released. Even with little or no evidence to suggest

they were involved, both men were in fact condemned to death. On hearing the

news the Professor’s wife, Madame Toumaian vigorously lobbied in the Houses of

Parliament trying to get assistance from the members for their release. Perhaps

bowing to external pressure, by August 1893 the Turkish authorities pardoned

Professors Toumaian and Kayayan and expelled them from the country. Toumaian

returned to England and settled in Essex with his wife and children. During WW1

Toumaian’s son, Armen signed up and fought in France against the Germans for

the British.

[5]

British Army WW1 Service Records, 1914-1920 for John Haig Arakelian – Personal

Statement

[6]

Armenian Settlements in India by Anne Basil, P.85.

[7]

Indian Engineering Vol. 31 by Patrick Doyle 1902.

23 February 2015

Manuk: From the Killing Fields of France to the Diamond Fields of Africa

Geoffrey Manuk’s Extraordinarily Short Life.

His Armenian pedigree stretches back several centuries with ancestors such as Khojah Phanoos Kalandar, Coja Sultan David Shameer, Astur Sarkies de Agavally, Ter Johannes Sarkies, Phanoos Bagram and Kevork ter Simon to name just a few, it is surprising to find that he was in fact baptised in a Scottish church in Calcutta, his parents clearly shunning the family history that was in his DNA.

Born in London 5th January 1894 to Percy and

Nellie Manuk he was baptised in St. Andrew’s Church Calcutta a year later[1].

|

| Birth certificate of Geoffrey Chater Manuk |

| ||

| Baptism record of Geoffrey Manuk at St. Andrew's Church, Calcutta |

A 2 x great grand nephew of Sir Paul Chater a philanthropist

from Calcutta, Geoffrey’s own father Percy was a renown barrister and art

collector who lived in Patna, India where he practised law. An only child he spent his early years in Calcutta. Like many young men

in India, Geoffrey applied to join the Indian Army, something that would give him a footing for the future. When the First World War broke

out he sailed for England to sign up.

He was assigned to the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

and by the end of October 1914 had been appointed with a temporary commission

as Lieutenant. Just a month later he was again promoted this time to temporary

Captain and by January 1916 he had been posted to the 7th Battalion

in France. He fought, marched, fought some more, saw many friends die in the

killing field and spent a year in the godforsaken trenches before returning to

England in February 1917. By May 1917 he was back in France. Extracts from the battalion war diary[2] for October

1917 give a snapshot of the life, conditions and routine that Geoffrey would

have encountered on the front line.

|

| War Diary of the 7th Battalion King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry Extract for October 1917 |

Place, Date, Hour

PROVEN, 1.X.17

In camp (P5) preparing for move.

On Route PROVEN TO BAPAUNE

2.X.17

Battn. Marched from camp to PROVEN RAILHEAD and entrained

11am for BAPAUME, arriving midnight.

BAPAUME-YTRES

3.X.17

Marched with transport to YTRES via ORCQUINEY arriving

about 6am. Remainder of day resting and changing camp.

YTRES-HAUT ALLAINES

4.X.17. 12.50p.m

Bn (with transport) left camp at 12.50 and marched to

HAUT ALLAINES via ETRICOURT, MANANCOURT & MOISLAINES, arriving at 2.30pm.

HAUT ALLAINES

5.X.17-7.X.17

Refitting and reorganising. Weather very wet. MAJOR LP

STOOR 12th KINGS, attached to Bn as Sec-in-Command to A/Lt-Col J.T.

Jenson 6/10.17.

HAUT ALLAINES0SOREL LE GRAND

8.X.17. 9am.

Embussed at MOISLAINES & debussed near FINS, marching

thence to Nisson Huts at SOREL, arriving noon.

SOREL-VILLERS GURSLAIN

9.X.17. 9pm

Relieved 21st Middlesex Regt. (40th

Divsn. 121st. Infy Bde) A B & HQRS at GUISLAIN (x2B9) & C+ D

Coys behind GONNELIEU (R26 c +d).

Continued to SUPPORT LINE 7 days, providing garrison;

also working parties for 7 SOM L.I. (right front coy) and 7 D.C.L.I. (left

front coy).

16.X.17. 8pm

A/Lt.Col J.T. JANSON left for 30 days special leave in

UK. Major LP STORR assumed command with Capt. R.G. ROYLE as Sec-in-Command.

GONNELIEU 16.X.17-22.X.17 Relieved 7 D.C.L.I. in left

front sector, with companies distributed as follows: Right Front B, Left Front

D, Right Support A, Left Support C. On the 19th there was an

inter-company relief, the support coys moving into front lines and the front line

coys into support.

17.X.17.

2/Lt. W. Short appointed ADJUTANT vice 2/LT R.C.W.

SMITHERS (killed in action Aug 16/17) from Aug 17th.

18.X.17

2/LT C. Ellis with a patrol of 18 D.R. lost direction and

entered a German trench. The party effected its escape leaving the officer

behind.

20.X.17. 10am

Court of Enquiry convened by MAJOR LP STORR assembled at

BN. HQRS. Members. CAPT. R.G. ROYAL (President), LT. N.D. GYE & 2/LT H.R.

PRUST. Instructions: to record opinion on “(I) Whether Sec.Lt. ELLIS is

missing, killed, prisoner of war or wounded and prisoner of war.

(II) Circumstances attending loss of Lewis Gun &

Three Rifles and culpability of men in charge of same”. After examining nine

witnesses, the Court found that 2/LT ELLIS must be wounded and a prisoner of

war. A qualified culpability was brought against men who abandoned Lewis Gun

& rifles.

VAUELLETTE FARM & RAILTON

22.X.17 – 29.X.17

Relieved in left front sub-section by 7 D.C.L.I. &

proceeded into RESERVE: hqr COY & a*c TO Vaucellette fm & b&d Coys to

RAILTON. Intensive training in musketry, bombing, PT & close order drill

was carried out with good results.

23.X.17

Bn took baths at HEAUDECOURT. Also on 27th.

26.X.17

Concer at HEUDECOURT arranged by Pdre. Rev. F.M. WINDLEY

(C of E).

27.X.17

Football match at MOUSLAINES. 62 field ambulance V. 7.

K.O.Y.L.I result Amb.4 K.O.Y.L.I. 1

28.X.17

Voluntary Church parades and working parties.

GONNELIEU. 29.X.17

Relieved 7 D.C.L.I. (less 1 Co) in left front sub-Sector

with Companies disposed as follows: right front “A”, Right Support “B”, Left

Front “C”. “D£ Co was at Fins assisting R.E.s.

30.X.17. 6am

“D£ Co relieved “C” Co. D.C.L.I. in Left Support.

31.X.17

Battalion extended its front to the left. Right support

co took over No. 1 Post R. Front Co. Right Front Co took over posts 1 & 2

L.F. co. Left Front Co took over posts from 10th K.R.R. bringing his

left to the GOUZEAUCOURT-CAMBRAI RD.

Due to illness Captain Manuk left the unit on 30th

October 1917 and headed for Rouen from where he sailed for England arriving on

the 16th November 1917. He was one of many to suffer P.U.O. commonly

known as trench fever, something that plagued hundreds of soldiers in France.

“Medical Officers

during World War 1 tended to put trench fever down as PUO - pyrexia (ie fever)

of unknown origin. Often they would take a stern view and prescribe

"M&D" - medicine and duty. The unfortunate soldier would be

returned to duty with some medicine, often the notorious Pill No. 9 (see

right). Pill No. 9 was a laxative beloved of the British Army doctor; it's

doubtful that it did much to help a man suffering with a fever.

Not all men

suffering with trench fever could return to duty, they were simply too ill. In

those cases, they would be evacuated to a hospital for rest and recuperation.

It's likely that many of them were in no rush to recover and rejoin their unit.

Trench fever, though unpleasant, was undoubtedly a welcome relief from being

shelled on the front line.[3]”

By January 1918 Geoffrey Manuk had been placed in a convalescing

home at Osborne on the Isle of Wight. In February of that year he wrote a desperate

letter to the War Office stating that he was still too unwell and not fit for

service. In April a report from Maudsley

Neurological Hospital in London recommended no further hospital treatment for

Capt Manuk but perhaps another 4 months spell at a convalescing home and

suggested he “may again be fit for sedentary duties at home”. However, that was

not to be and he relinquished his commission on account of his ill-health on

the 19th June 1918. He was

granted the honorary rank of Captain.

He was awarded the British War and Victory medals on the

21st December 1921.

|

| Geoffrey was awarded the British and Victory war medals |

After the end of the war he can be found living in Iverna

Court, London in 1919, ironically not far from the Armenian Church.

|

| Geoffrey was living close to the Armenian Church in London |

In the early 1920’s having recovered from the illnesses

that had cut his war service unexpectedly short and perhaps yearning for some

warmth on his body and maybe a safer adventure for his heart, he can be found

in South Africa as a diamond digger. A bachelor with no commitments, he might

have thought it would be a good way to make some money. It was in fact a brutal

way to earn a living, the searing heat and basic conditions of the mines were

not for the faint hearted. He didn’t last long and on the 19th

October 1924 at Droogveld, Sydney-on-Vaal in Barkly West he died aged 30 years

and 9 months. Having been through the very harrowing and bitter times of WW1 in

Flanders, he met his death in the harsh scrub land of the South African desert

panning for diamonds. His debts amounted

to £100 (sterling) which were paid by his father, P.C. Manuk. The list of

possessions as noted in his estate inventory show the very bare minimum he had

with him[4].

|

| Geoffrey's Estate Papers are held at the Cape Town National Archives |

1 silver wristlet watch

1 pocket compass

1 wood and canvas stretcher bed

1 box kitchen utensils, Beatrice and primus stoves

1 cabin trunk containing clothing

1 leather suitcase, containing clothing

1 bundle of clothing, etc. & helmet

1 leather writing satchel and contents

1 box boots (3 pairs)

1 box sundries (shaving and toilet requisites etc)

1 square tank (wood and iron) 6' x 4'

1 house (since smashed by the wind) 8' x 9'

1 single bebe

1 overcoat (gents)

He is buried at the Old Mine Cemetery, Sydney on Vaal,

Delportshoop, Barkly West District, Northern Cape, South Africa.[5]

|

| Buried in the Old Mining Cemetery at Sydney on Vaal, South Africa |

Photo courtesy of: Gansie Coetzee, South Africa

Via website: The Genealogical Society of South Africa eGSSA branch

My

thanks and acknowledgments go to Gansie Coetzee and the Genealogical Society of

South Africa for photographing and recording the graves at the Old Cemetery,

Sydney on Vaal (rural farm cemeteries) where Geoffrey Chater Manuk is buried. A simple tombstone and taking into account the harsh sun and dusty conditions in the African veld, it has a remarkably readable inscription.

There are no Armenians in Sydney on Vaal and it is likely that his grave has never been visited by family or friends - maybe one day someone will.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)