This story is brought to you with the support of the

AGBU UK Trust.

AGBU UK Trust.

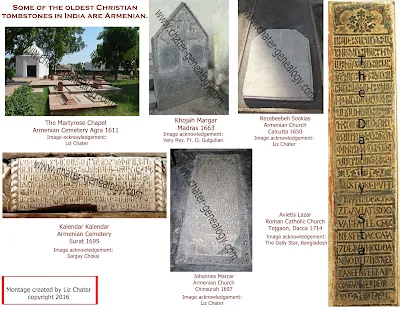

Some of the oldest Christian graves and tombstones in India and Bangladesh are Armenian.

*NOTE:

The hyperlinks in square brackets [ ] do not work in this blog, please scroll

to the bottom to read the links.*

Madras

For many a tourist, the start of an afternoon’s visit to a small church in Chennai begins at the foot of a large flight of stone steps, leading on to the Little Mount Catholic Church of ‘Our Lady of Good Health’. Already they have missed a significant monument of historical importance, one that has been written about many times, but for some reason not popular enough to photograph and record as they eagerly climb up to visit the wonders of the church and its caves. The language is unfamiliar to many, the script tricky for locals to read; Armenian history is at their feet as the daily routines of people pass by. It is the oldest Christian grave in Madras, and it is Armenian.

Forgotten.

But not any longer.

|

| Images courtesy of Very Rev. Fr. Oshagan Gulgulian |

A record of the inscription can be found in at least two books, Mesrovb

Seth’s ‘Armenians in India’ as well

as a ‘List of Inscriptions on Tombs or

Monuments in Madras’ by Julian James Cotton, but no images have so far made

it in to the public domain.

Described as a milestone in shape, and perhaps maybe even mistaken as

such in this busy city, the tombstone, dated 1663 of Khojah Margar, is one of a

handful of the oldest Christian graves in India that happens to be Armenian.

The others can be found in Surat, Agra, Calcutta, Chinsurah and Dacca respectively.

For those interested in knowing about the other centuries old Christian

graves and monuments in India that are Armenian, here is a brief summary.

Agra

The Martyrose Chapel

|

| Images from the private archive of Liz Chater |

I expected the Armenian cemetery at Agra to

be a little worse for wear and care, but I couldn’t have been more

mistaken. It is incredibly well

preserved and conserved by the local Agra authorities, the grounds and

shrubbery are well kempt and some of the stones and their inscriptions look as

fresh and clear as the day they were carved.

Mesrovb Seth writing of the Martyrose Chapel

said: “This Mausoleum which is not built

of marble, like the world-famed

Taj, is nevertheless the oldest Christian

structure in Northern

India. It was erected in 1611 at the old Armenian Cemetery”.

Agra Municipality are clearly showing their

sympathies towards these beautiful historic stones and structure, making

wonderful efforts in creating an attractive location for tourists to visit.

|

| Image courtesy of Liz Chater’s private archive |

Although not the original stone, there is a

marker inside the chapel remembering the earliest Armenian burial in Agra, Khwaja Mortenepus, 1611.

Calcutta

Probably the most well known in the group of

oldest Christian tombstones, is situated at the Armenian Church in Calcutta. A

modern day plaque in English placed there in 1971 rests upon an 18th

century intricately carved stone, bearing an inscription and date of 1630. “This

is the tomb of Rezabeebeh, the wife of the late charitable Sookias, who

departed from this world to life eternal on the 21st day of Nakha in the year

15 i.e., on the 21st July,

1630.”

It is in the compound of the churchyard

where other interesting tombstones and inscriptions can be found.

|

| Image courtesy of the private archive of Liz Chater |

Chinsurah

The Armenian Church in Chinsurah is the second oldest church in Bengal.

It was erected by the Marcar family. Johannes Marcar laid the foundation for

the church in 1695. He died just two years later and was buried inside the

church. Protected from sun, wind and rain, it is in wonderfully good condition.

|

| Image courtesy of the private archive of Liz Chater |

The transcription is a combination of Mesrovb Seth’s work and present

day scholar and historian Sebouh Aslanian to whom I am most grateful for his up-to-date translation: THIS

IS THE TOMB WHEREIN LIES INTERRED THE FAMOUS QARIB [GHARIB OR

STRANGER/WANDERER] CALLED KHWAJA JOHANNESS, THE SON OF MARCAR OF JULFA, FROM

THE CITY OF SHOSH. HE WAS AN EMINENT MERCHANT, HONORED BY KINGS AND RESPECTED

BY PRINCES. HE WAS HANDSOME AND AMIABLE AND HAD TRAVELED SOUTH, NORTH, WEST AND

ALL THE FOUR CORNERS OF THE WORLD. HE DIED SUDDENLY, ON 27TH DAY OF NOVEMBER,

1697 IN THE EASTERN PART OF THE COUNTRY, AT THE CITY OF HUGLI, AND DELIVERED

HIS SOUL INTO THE HANDS OF THE ANGEL AND RESTED HERE WITH NOSTALGIA FOR A HOME.

THE END OF

THE WORLD SHALL COME, THE CROSS OF THE EAST WILL DAWN, THE TRUMPETS OF GABRIEL

WILL BE BLOWN SUDDENLY IN THE MIDDLE OF THE NIGHT, THE SEAT OF JUDGMENT WILL BE

SET UP THAT THE BRIDEGROOM SHALL COME AND SIT THEREON AND SAY "COME YE THE

BLESSED OF THE HEAVENLY FATHER." AND MAY HE DEEM HIM [KHWAJAH JOHANNESS

MARCAR] EQUALLY WORTHY LIKE THE FIVE WISE VIRGINS, TO BE IN READINESS TO ENTER

THE SACRED PAVILION WHICH ONLY THE RIGHTEOUS THAT ARE ON THE RIGHT, CAN INHERIT.

OH YE WHO

MAY COME ACROSS THIS TOMB PRAY FOR HIM EARNESTLY AND MAY GOD HAVE MERCI ON YOUR

PARENTS AND ON ME, REVEREND GREGORY WHO AM A NATIVE OF ERIVAN. HERE ENDETH THE

TRANSCRIPTION."

Surat

In January 1907 when Mesrovb Seth was

travelling around India recording Armenian

tombstones and gathering research material for his book, he visited the

Armenian cemetery in Surat. There he

came across a tombstone of an Armenian lady who died in Surat in 1579 A.D.

Having seen the stone, Mesrovb Seth gave the

following inscription, translated from ancient Armenian verse,

"In this

tomb lies buried the body of the noble

lady, who was

named Marinas, the wife of the priest

Woskan. She

was a crown to her husband, according

to the

proverbs of Solomon. She was taken to the Lord

of Life, a

soul-afflicting cause of sorrow to her faithful

husband, in

the year one thousand and twenty eight of

our Armenian

era, on the fifteenth day of November at

the first

hour of Friday, at the age of 53.

Ye who see

this tomb, pray to the Lord to grant mercy.”

The year 1028 of the Armenian era is

equivalent to the

year 1579 A.D.

Sadly, it would seem that this particular

stone is no longer visible, or perhaps has simply been overlooked. The cemetery

is being well cared for by the Surat Municipality and monitored by the Science

Museum and I know the museum regularly check the condition of the stones. The

staff are very proud and tremendously passionate about the treasures in their

care. However this particular grave does not appear to be in their inventory.

The oldest surviving marker stone is in the

Mortuary Chapel at Surat belongs to the late Kalendar Kalendar, carved on what

looks like a piece of ancient wood, and, according to Seth says:

This is the tomb of

Kalandar, the son of Phanoos Kalandar of Julfa, who departed this life on

Saturday, the 6th day of March 1695.

|

| Image courtesy of Sanjay Choksi Surat Science Museum |

Thank you Surat for the care and

preservation you do for the remaining Armenian tombstones.

Dacca

Inside the Roman Catholic church (Note: Not the Armenian church) of "Our Lady of

Rosary," at Tejgaon, two and half miles from Dacca, on the Dacca-Mymensingh

Road, built in 1677, there are some old graves of Armenians who died at Dacca

between the years 1714 and 1795.

|

| Image courtesy of The Daily Star, Bangladesh from a series of articles on the Armenians in Dhaka, June 2013 |

The oldest Armenian marker in the cemetery is this

one: “This is the tomb and resting place

of Avietis the merchant, who was the son of Lazar of Erivan, whom may Christ

and His Second Advent find worthy of His presence. In the year 1714 August 15[1].”

Referring once again to Mesrovb Seth’s ‘Armenians In

India[2]’, he notes that, “there

is also an inscription in Portuguese, in which the date of his death is given

“7 de Junho” (7th June). We cannot account for this discrepancy, but

we are inclined to think that the date given in the Armenian inscription is the

correct one, as the old Armenians were very particular about dates.”

It is sad that more of the very old Armenian stones

and markers in India, Bangladesh and SE Asia have not survived the years, but

at the same time we are very lucky that many still do survive and are falling

under the protection of relevant bodies that recognise their significance in

the combined history of India and Armenia.

Important historical graves exist today in

the Armenian Church at Dhaka. My book,

“Armenian Graves Inscriptions and Memorials in India: DACCA” is the first

publication to catalogue in full the remaining tombstones in the Armenian

language with English translations. For many years they were locked in the

beautiful ancient Armenian language but accessible only to a limited audience.

This book releases these astonishing inscriptions to the world-wide family

history researcher and for the first time, allows them to trace their Armenian

ancestry in Bangladesh.

To preview a selection of pages or purchase

the book, please use the link.

If you ever find yourself in Chennai, take a

visit to The Little Mount but look for Khojah

Margar before you climb the steps to the caves.

[1]

Full transcription extracted from Bengal Past and Present short article on the

Armenian Church of Dacca, 1916.

[2]

Armenians In India P.571. For a free download of this out of copyright

publication https://archive.org/details/ArmeniansInIndia_201402